Thursday, December 21, 2023

Climate Justice and Water

Sunday, December 10, 2023

COP28: Water as a priority or in the peripheral

What is COP28?

Sincere Promises?

Transboundary Water Management: Beyond Traditional Territories

Contesting Borders: Basins and International Boundaries

Previously I explored water dependency on local and national scales; however, I have yet to discuss the complexities of the form of water management that transcends geographical boundaries. A fundamental constraint to the sustainable management of water resources on the continent is the fact that 68 water basins are transboundary in nature (Kotzé 2022). The Nile and Congo basins exemplify such, with their boundaries transcending nine countries (see Fig 1) (Del Pietro 2002). While the utilisation of basin resources and provisioning services varies spatially, the lack of unified, international management strategies poses implications for water scarcity and conflict mitigation (Gaye & Tindimugaya 2018).

Interdisciplinary Solutions to TWM

Saturday, December 2, 2023

National to Local: The Realm of Water-Based Power

Small yet powerful applications

In the context of hydroelectricity, there is a misconception that projects have to be large-scale to yield widespread benefits. As discussed in my previous post, hydroelectric projects are vulnerable to the fluctuating water patterns that arise with environmental change. Nevertheless, transitioning our focus from national to local could be an unprecedented mitigation strategy for sustaining water and energy security. I would like to commence with a powerful video that explores the accomplishment of John Magiro Wagare in his construction of a small-scale hydropower installation.

Figure 1: Video explaining the hydropower success story of Njumbi, Kenya (Great Big Story 2018)

John utilised his experience as an electrician to harvest energy from the River Godo and produce a small-scale hydro-plant constructed from repurposed materials. The establishment of Magiro Power enabled a community-wide transition towards renewable electricity as a substitute for costly, polluting alternatives (Great Big Story 2018). In this case, the use of water to facilitate a turbine mechanism ensured energy provision for over 250 households; exemplifying the potential for small-scale hydro projects to generate durable impacts.

The geographical feasibility of mini-hydropower

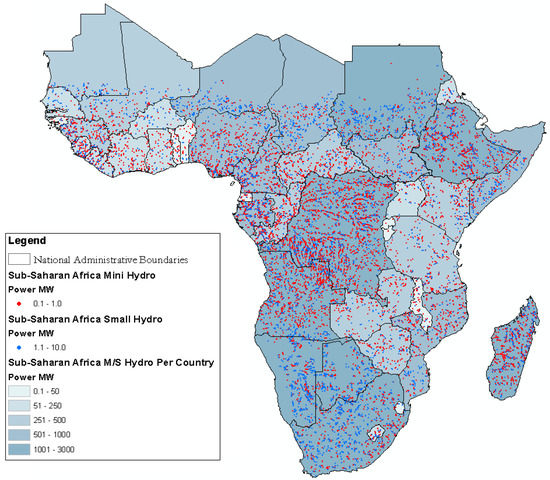

While population growth can coincide with a greater urban population ratio, a range of countries in SSA have displayed rural population increases in recent years (Drangert et al. 2002). These demographic patterns encourage a consideration of water management at the local scale, especially in areas where decentralised hydroelectricity could address infrastructural limitations (Falchetta et al. 2019). Korkovelos et al. (2018) conducted a fascinating analysis of the small-scale implementation of hydropower plants throughout SSA. The insights revealed the astonishing potential to generate 9.9 GW of installed capacity in the Southern Africa region alone. Beyond this, they used geospatial analysis to identify 10,216 sites where mini-hydropower initiatives could be established (Korkovelos et al. 2018). To provide some context to what defines 'mini', John's hydroelectric plant in Njumbi, Kenya yields a capacity of 0.25 MW, which is within this range (0.1-1MW). Now imagine the implications of replicating his initiative to thousands of other contexts!

Figure 2: Identification of potential sites for variably sized small-scale hydropower initiatives in Sub-Saharan Africa. Adapted from Fig 7 (Korkovelos et al. 2018)

The mass realisation of hydropower on a small-scale requires an adaptation of political mindsets, as well as innovative approaches to material circularity and renewable energy. In times where mass hydro-projects are anticipated to worsen water security and generate mass community displacement, these sustainable solutions could be vital towards climate and water resilience in SSA (Machado 2023).

Climate Justice and Water

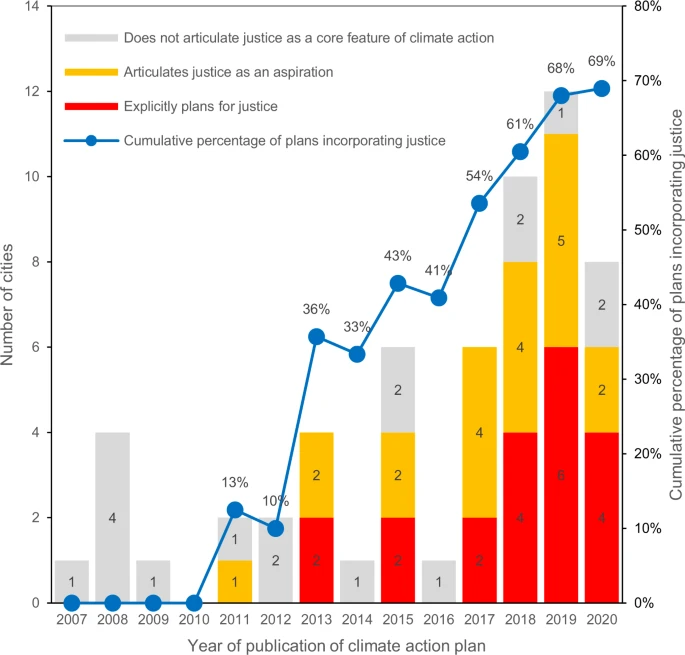

What is Climate Justice? Climate justice is a term that stimulates discussions on legacies of inequality and colonial exploitation (Williams...

-

Contesting Borders: Basins and International Boundaries Previously I explored water dependency on local and national scales; however, I hav...

-

Community Water Management When confronting the topic of climate change, an approach typically suggested to improve water access at the loca...

-

What is COP28? This post is a slight deviation from my projected narrative, but I thought it would be important to shed light on the ongoing...