Hydroelectric Dependence on Water

While my previous entries have focused on the consumptive aspects of water, this article will address the role of the resource as a facilitator. Water retains vast importance as an input for agricultural, industrial, and domestic applications; however, an additional realm with huge reliance on the resource is electricity production (Yamba et al. 2011).

Figure 1: Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam situated along the River Nile (Hailu 2022)

Hydropower presents a fascinating case for renewable energy transitions, for it is a mature concept that has experienced rapid innovation and application in recent years. For those unfamiliar to the term, hydropower is a means of electricity generation that utilises the kinetic (moving) and potential (height-based) energy of water . In theory, the technique would be ideal for energy transitions on a global scale; however, the installation of hydroelectric dams is entirely reliant on hydrological compatibility. Compatibility is exemplified throughout the Sub-Saharan African region, where hydropower accounts for over 50% of national electricity production in certain countries (Falchetta et al. 2019) (see Fig 2).

Figure 2: Hydroelectricity share in national electricity production for 2020 (Zandt 2022)

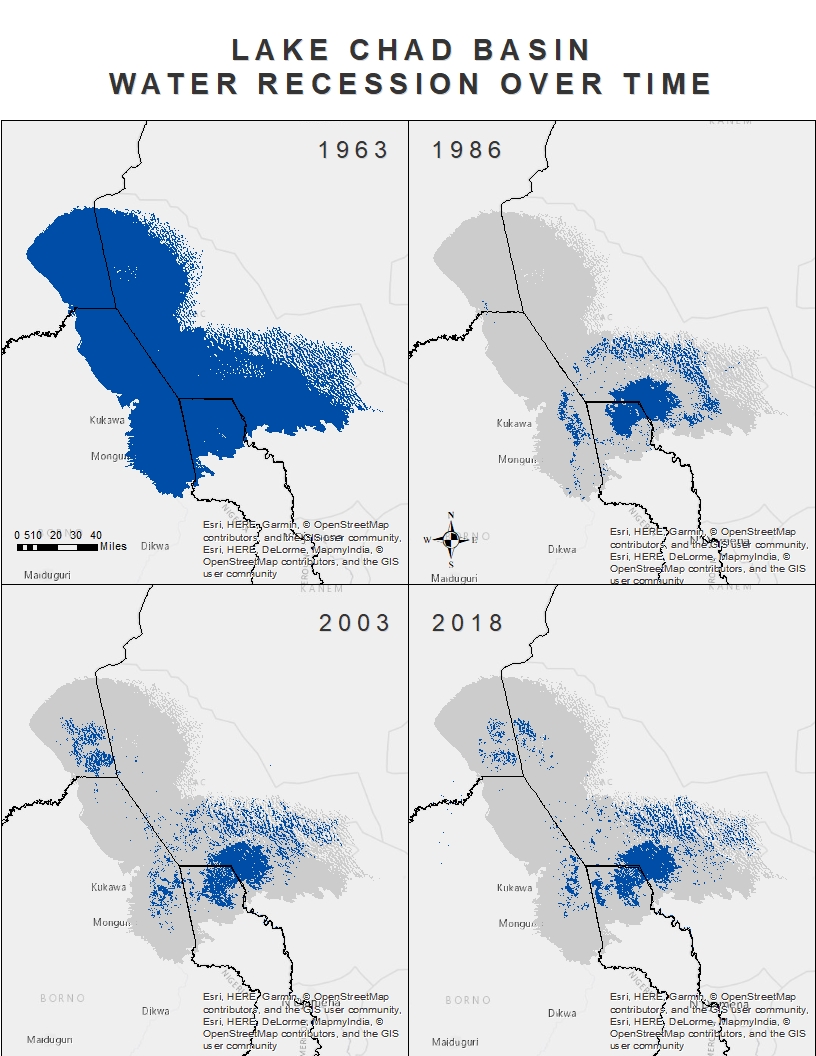

Climate Change Vulnerability

While the abundance of hydropower on the continent is commendable, the long-term resilience of this production strategy is threatened by environmental change. Climate change presents the risks of extended drought periods and variable precipitation patterns (Yamba et al. 2011). Each of these factors significantly inform the river flow regimes and reservoir storage upon which hydroelectric productivity is dependent on. Beyond the discernible, climate change heightens the uncertainty surrounding inequalities in water and energy access.

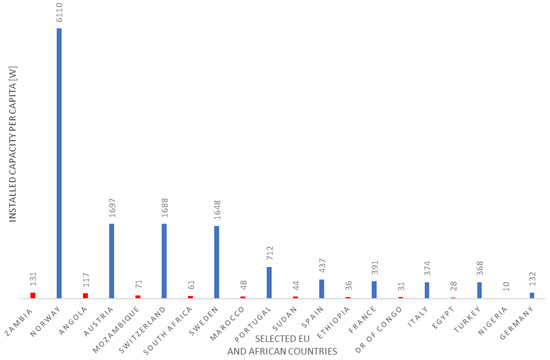

Figure 3: Comparison of installed hydropower capacity per capita for largest African and European producers (Borowski, 2022)

Borowski (2022) revealed that of the ten largest producers of hydropower on the African continent, Zambia achieved the highest installed capacity per person, at approximately 131 Watts (see Fig 3). Initially this value appears adequate, yet if you return to the previous figure, an unforeseen component of the statistic is revealed. Over 81% of national electricity production is derived from hydropower in Zambia. While it should not be assumed that electricity consumption is homogenous, these statistics emphasise an extremely low production capacity relative to the population that it aims to sustain. The severity of such is predicted to worsen with rising population rates and hydroelectric vulnerability; however, there are numerous mitigation strategies that aim to minimise these implications (IEA, 2020).

Moving Forward...

The following blog post will delve further into mitigation strategies and adopt a more optimistic stance on hydropower relative to climate change. I look forward to sharing the captivating potential of local and small-scale hydropower initiatives for the improvement of both water and energy accessibility.